A rigid arm

A rigid arm

Block(1.0, 0.1, 0.1) : (color="red") { // this block is long along X

Translation(0.5,0,-0.5) { // blocks intersect at (0.5,0,0)

Block(0.1, 0.1, 1.0) : (color="green"); // this block is long along Z

}

}

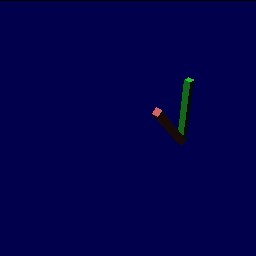

Following the robotics standard, revolute joints rotate about the Z axis. For this reason, you must often rotate in and rotate out if you want to place a revolute joint in an existing design. Let's do this for the above arm, previously rigid.

Translation(-0.5,0,0), // translate to endpoint of bar Rotation(1,0,0,-pi/2), // rotate Z so it aligns with world Y RevoluteJoint, // place a joint Rotation(1,0,0,pi/2), // rotate back Translation(0.5,0,0) { // translate back Block(1.0, 0.1, 0.1) : (color="red", mass=1) { Translation(0.5,0,0), // do half our translation Rotation(1,0,0,-pi/2), // rotate Z so it aligns with world Y RevoluteJoint, // place a second joint Rotation(1,0,0,pi/2), // rotate back Translation(0,0,-0.5) { // translate to center of second block Block(0.1, 0.1, 1.0) : (color="green", mass=1); } } }

To get the links to move, you must have an active gravity, and you must give the links non-zero masses.

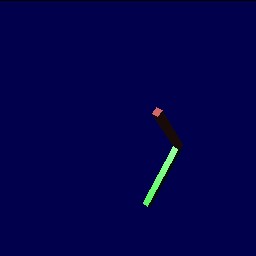

Double pendulum, 1 sec

Double pendulum, 2 sec

Double pendulum, 3 sec

The code for the second example looks a little hairy, but it can be cleaned up very easily if we rotate into the joints' coordinate frames, and never rotate out. I did the above to show that we can use the same blocks as in our previous example.